You can read the Serbian translation here.

Introduction

More than one year and a half after the global pandemic of COVID-19 started, although we finally may say that we do feel some relief, the end of it is still far from being certain. But, what is even more uncertain are its consequences, social, political and economic ones, and the way they are affecting and are going to affect mental health, both locally and globally, in a world that has already lived in a state of deep crisis for decades. In this world, Pope Francis’s new encyclical Fratelli tutti1 , by strongly emphasizing necessary social and political meaning of Christian virtues and values of charity and panhuman fraternity, shines like a true light in the darkness, like a respite of which Abba Macarius was told by a skull in the desert, as you will read below.

Religion and Mental Health

From the historical point of view, the concept of mental health is both in positive and negative terms very much intertwined with religion. We might say that, up to the modern age, there was no other treatment of what we now know as mental illnesses apart from the one offered by religion. Of course, in many cases superstition and brutality prevailed (they always come together, indeed); but, again, we may still look into religious tradition and find many inspiring examples that might help us solve some important problems regarding the mental health issues.

The most important ones are, we find, those connected with interpersonal and social context of both their etiology and treatment. In this aspect we come very close even to the modern schools of critical thinking about the mental health issues (such as Anti-psychiatry) that have done much to raise the awareness about the importance of (patho)social mechanisms, such as domination, stigmatization etc., for understanding and dealing with the mental health issues (cf. Classen 2014, Shumaker 1992, Szasz 1997). Especially in this respect, from the Christian point of view, we find inspiring and important narratives already in the New Testament. Of course, in all of them the state of illness is described as a work of demons and the act of healing always comes in the form of exorcism. But if we consider complex symbolism of demonic language and imagery in general, as well as those different layers of meaning more or less apparently contained within the texts, then a whole new world of ideas comes to us.

What is of central importance for us here, especially regarding the subject of our small survey, is that these ideas are always substantially dependent upon the core anthropological message of Gospel, and that is the panhuman fraternity in the perspective of ontological and soteriological unity of all in Christ. Of course, these texts also reveal what those obstacles placed by the prince of this world (Jn. 12.31) are, on our road towards this unity which is the Kingdom of Heaven.

The Source of Inspiration: NT Exorcism Stories and Our Demons

Here we may consider two well-known stories about healing that we find in synoptic gospels, the exorcism of a gentile woman’s daughter (Mt. 15. 21-28; Mk. 7.24- 30) and the famous story about the healing of the Gadarene/Gerasene/Gergesine demoniac2 (Mt. 8.28-34; Mk. 5.1-20; Lk. 8.26-39).

Compared to all others NT exorcism stories, the second one is especially important because we may interpret it as a very powerfull critique focusing on the social aspect of our problem3 . What is also very important about NT exorcism stories in general is that there is no place for individual guilt as the explanatory mechanism. Those possessed are not guilty of their possession. The somehow enigmatic answer, given in one other famous healing occasion and described in the Gospel of John (chapter 9), applies in all these cases directly: “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind? Jesus answered, Neither this man nor his parents sinned, but that the works of God should be revealed in him” (Jn. 9.2-3).

The Exorcism of a Gentile Woman’s daughter

Now, let us briefly discuss the first above mentioned story. A gentile women, Canaanite according to Matthew or Greek of Syrophoenician origin according to Mark, came to ask Jesus to cast out the demon who tormented her daughter. The little possessed girl was not present. What is striking is that Jesus at first gives her the answer full of what in modern terms we may describe as both racism and nationalism, namely, he tells her to go away because Gentiles are dogs (Mt. 15.26; Mk. 7.27).

Of course, his words just set the scene for what is central in this story and what, according to Jesus himself, effected the exorcism and healing – her faith: “Woman, great is your faith! Let it be done for you as you wish”, according to Matthew (15.28), or “For saying that, you may go – the demon has left your daughter”, according to Mark (7.29).

Now, this faith is not revealed in her initial confession of him as Messiah, that we find in Matthew (15.22), but in her refusal to play by the rules of a world divided by tribalistic and racist hatred. She knew that the Son of God is not of that world, contrary to what she herself heard at the very moment, and she decided to play his role. That is why her refusal was not desperate and passive, but active – the only way to defeat hatred is love. Therefore, she accepted to be a dog for the love of her daughter, and that was what effected exorcism, as Jesus himself said, that was her faith (cf. In Mattheum Hom. LII. al. LIII.2).

Now, let us look, from the perspective of this story, to our modern context and the problems we are dealing with. The most common form of psychiatric disorder in our region, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina, is the Posttraumatic stress disorder, which is, of course, a direct consequence of war traumas.

According to various current statistics, up to 40% of citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina are suffering from this disorder or have shown some of its symptoms. What is even worse is that PTSD may sometimes be transmitted to younger generations which were not directly exposed to traumatic events4 . It is often said that our society is one living in the state of a frozen conflict (Valić Nedeljković et al. eds. 2017).

Our reality is a kind of brutal affirmation of Foucault’s famous maxim, which reversed the one even more famous of Von Clauzewitz, namely, that politics is the continuation of war by other means5 . As time passes, it more and more seems that manipulative potential of interethnic tensions – that same demon which gentile woman had faced and defeated in front of Christ – is an indispensable tool, and often the favorite one, in the hands of political elites in our region. And when it comes to interethnic tensions, one can’t avoid religion, since it is seen as the most important identity marker (and often the only one).

Therefore, regarding our topic – how religion, by promoting the idea and principle of global fraternity, may contribute to mental health – we can say that it is obvious what we have to do. Before we come to promote global fraternity among humans, we must promote the regional one, because that is where we all failed and what has to be healed first.

That is also what generates and perpetuates trauma which causes not only PTSD but also many other disorders, both mental and social ones. To do so, we have to face our own religious reality first. We have to ask ourselves how it came to be that religious communities here are often and rightfully seen as the strongholds of nationalisms and antagonisms of each and every kind? To speak of and preach global fraternity while looking at our neghbour or brother who speaks the same language as we do with hatred in our eyes is hipocrisy, of which many words were written in our sacred books.

Therefore, to find the inspiration to change this, we just have to look into these books and read them with both mind and heart; to find the reason, we just have to look around ourselves and see the demonic nature of reality which we live. That is how we come to the second story mentioned above, the one about G. demoniac. We think that this story may give us some answers to the question about psychological and social mechanisms that produce and perpetuate demonic possesion of our everyday life. So, let’s remind ourselves of the story first.

The Healing of the G. Demoniac: Demon of Scapegoating

In the surroundings of the city of G., close to the Sea of Galilee, there was a man possesed by a demon. He lived in the tombs and was so fierce that no one could tie him down, even with chains – he would simply break all fetters and chains. “And always, night and day, he was in the mountains and in the tombs, crying and cutting himself with stones“ (Mk. 5.5).

When Jesus approached him to cast the demon out – although nobody asked him to do so, which is strikingly different from all other similar stories in the gospels – the famous dialogue between him and the demon occured.

According to the most elaborate account, found in Mark, the story goes further like this: “What is to me and to You, Jesus, son of the Most High God? I adjure You by God not to torment me. For He said to him, Come out of the man, unclean spirit! And He asked him, What is your name? And he answered, saying, My name is Legion, for we are many. And he begged Him very much that He would not send them outside the country. And a great herd of pigs was feeding near the mountains. And all the demons begged Him, saying, Send us into the pigs, that we may enter into them. And immediately Jesus allowed them. And the unclean spirits went out and entered into the pigs. And the herd ran violently down a steep place into the sea (they were about two thousand), and were choked in the sea. And the ones who fed the pigs fled and told it in the city and in the country. And they went out to see what it was that was done. And they came to Jesus and saw him who had been demon-possessed, and had the legion, sitting and clothed and right-minded, the one who had the legion. And they were afraid. And those who had seen told them how it happened to the one who had been demonpossessed, and about the pigs. And they began to beg Him to leave their borders.”

Now, for our discussion here we will follow one modern and well known interpretation given by famous french anthropologist and polymath René Girard. Following Girard, we will try to answer how this well known gospel account may be interpreted from the point of view of collective or social psychopathology and, potentialy, what it has to do with our regional and global context concerning the subject which we discuss here.

According to Girard, “humanity is imprisoned in a system of mythological representation of a victim… who is made sacred because of the unanimous verdict of guilt” (Girard 1986, 166), that is by the scapegoat mechanism (remember what is said above about guilt as the explanatory principle). This system or mechanism is based on “a false transcendence” generated by mimetic mechanism of desire.

“Mimeticism is the original source of all man’s troubles, desires, and rivalries, his tragic and grotesque misunderstandings, the source of all disorder and therefore equally of all order through the mediation of scapegoats” (Girard 1986, 165). Completely in accordance with biblical teaching of man as the image of God (Gen. 1.26) and with much of modern psychology as well, Girard emphasizes that humans are beings of imitation.

Of course, this has both positive and negative aspects. We come to know ourselves by interaction with other people – we always have some model or a paradigm, some kind of hero. But we also imitate other people’s desire – and not only do we wish to have or own what others have or own; we want to be them in their act or state of having or owning, and in order to do so (which is, of course, impossible and therefore false) we must eliminate them. That is the essence of mimeticism; we could say that it is a kind of ontological envy.

This is exactly what makes scapegoating necessary. Had there not been a scapegoat, everything would have turned into bellum omium contra omnes. Therefore, unanimous verdict of guilt is that means by which violence of all against all, that would otherwise dominate the world of mimeticism, is being transfered and turned into a cohesive force of community based upon it. The unbearable sense of guilt is eradicated through violence over an innocent victim. But it will necessarily return, since the mimetic mechanism that produces it is still the main driving force of the community founded in the act of original scapegoating.

One should note that Girard’s ideas about desire could be parallelled with similar concepts found in the tradition of Christian ascetic thought, but also in great ancient schools of moral philosophy which influenced Christian asceticism heavily, such as stoicism. Here we call to our mind fundamental stoic and Christian doctrine on virtues and passions (pathoi). But what makes Girard’s system special is the fact that he understood the fundamental social role these mechanisms play, the awareness of which is, he thought, already present in the earliest Christian texts, namely, in the New Testament.

This is how we come to Girard’s more than instructive explanation and definition of Satan and demon(s). Namely, false trancendence generated by mimetic mechanisms is what Girard says is Satan. “When the false transcendence is envisaged in its fundamental unity, the Gospels call it the devil or Satan, but when it is envisaged in its multiplicity then the mention is always of demons or demonic forces. The word demon can obviously be a synonym for Satan, but it is mostly applied to inferior forms of the power of this world; to the degraded manifestations that we would call psychopathological” (Girard 1986, 166). In the strange set of circumstances about G. demoniac Girard recognised all important traits of the scapegoat ritual. There is one that stands before all, expelled and set apart, but still essentially close to them; he is the object of their constant violence, extreme but at the same time passive violence.

This type of passive violence, following patterns of the NT thought, may be rightfully defined as hypocritical (cf. e.g. Mt. 23). What demoniac does by the strange act of autolapidation is that he reveals true nature of his fellow citizens’ relation to him and their hypocrisy. Finally, the climax of the story is the very act of execution – by the fall from the cliff, but after roles were reversed. But, what is especially important to note is that in this story the scapegoat ritual is being literally perpetuated – it is not an excess, but a kind of pathological routine.

“Mark’s text suggests that the Gerasenes and their demoniac have been settled for some time in a sort of cyclical pathology. Luke gives it even greater emphasis when he presents the possessed as a man from the town and tell us that a demon had driven him into the wild only during his bad spells” (Girard 1986, 169). This indicates directly towards Girard’s main thesis: scapegoating is not an excess, but demonic foundation of human societies throughout history.

This interpretation also explains an important exegetical issue regarding this text. What we have in mind is the somehow strange, comparing to other similar stories, citizens’ reaction after they understood what Jesus had done. In all three gospel accounts it is said that they were afraid and that they begged him to their country, after they saw their fellow citizen “sitting at the feet of Jesus, clothed and in his right mind“ (Lk. 8.35).

Here we find stunning parallel between their words and those of demons who begged Jesus “not to send them outside the country“ (Mk. 5.10). But the parallel between citizens and demons is not just in this words; the principle of mimetic doubles is found throughout these texts. According to Girard, it is precisely because of this that Matthew introduces one more demoniac into his account: “He wants to suggest what we ourselves have learned during our readings. Possession is not an individual phenomenon; it is the result of aggravated mimeticism. There are always at least two beings who possess each other reciprocally, each is the other’s scandal, his model-obstacle. Each is the other’s demon; that is why in the first part of Matthew’s account the demons are not distinct from those they possess” (Girard 1986, 172).

This last point is crucial because the same may be applied to the relation between demons and the citizens. Citizens did speak on behalf of demons when they asked Jesus to leave, after he had reversed the ritual by letting herd of pigs be executed by suicidal jump from the cliff. Let us quote Girard once more: “Since all coexistence between Jesus and the demons is impossible, to beg him not to chase away the demons, when one is a demon is the same as begging him to depart, if one is from Gerasa. The essential proof of my thesis that the demons and Gerasenes are identical is the behavior of the possessed insofar as he is the possessed of these demons. The Gerasenes stone their victims and the demons force theirs to stone themselves, which amounts to the same thing. This archetypal possessed mimics the most basic social practice that literally engenders society by transforming mimetic multiplicity in its most atomized form into the strongest social unity which is the unanimity of the original murder. In describing the unity of the multiple, the Legion symbolizes the social principle itself, the type of organization that rests not on the final expulsion of the demons but on the sort of equivocal and mitigated expulsions that are illustrated by our possessed, expulsions which ultimately end in the coexistence of men and demons” (Girard 1986, 182).

Living in a Possessed World

If we speak about a possibility that the promotion of religious teaching on human fraternity positively affects mental health in global terms, especially in a world so bitterly shaken by the continuity of crisis that culminated in global pandemics, what we must do first is to face our reality and try to name it in terms of our belief. This is exactly what, we believe, Girard’s interpretation of the story about G. demoniac helps us to do. Indeed, we live in a world where men and demons coexist. Wherever there is scapegoating there are men and demons mixed up. And if we look at ourselves we can see that precisely this is the situation we are facing, both regionally and globally.

Mutual scapegoating is the way we live our little regional narcissistic hell of minor differences (cf. Freud 1962, 61) for decades now. That is what constantly produces demoniacs and lunatics of all kind, these are demons that we have to cast out from their men, starting from ourselves. Globally, the massive expansion of information technologies at the beginning of the 21th century, contrary to the expectations of many, has become a catalyst for the emergence of the new forms of violence and the enhancement of those traditional ones.

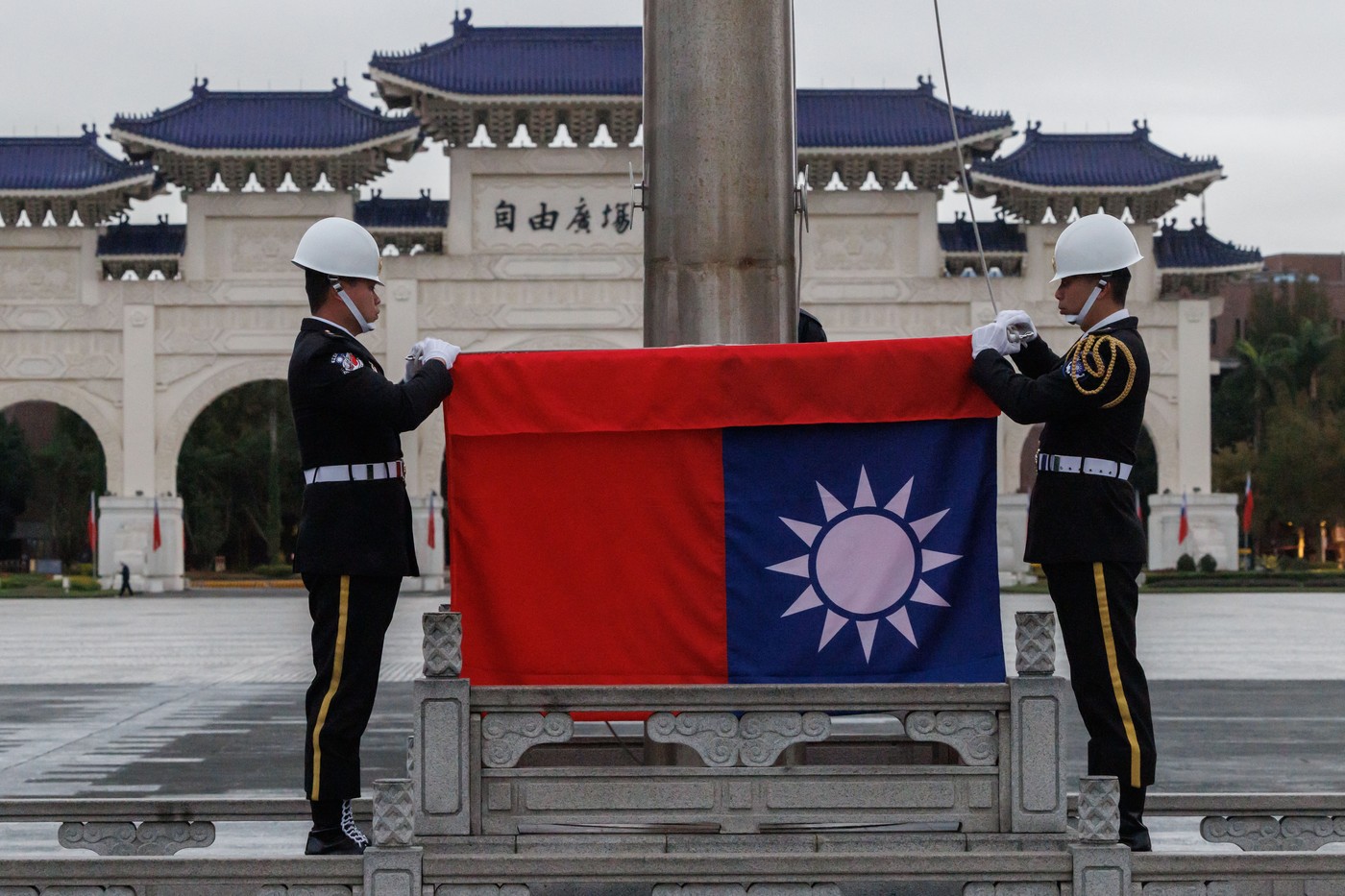

What was meant to be a space of freedom has become a source of constant violent manipulation, traumatization and retraumatization. One might say that the Legion has finally found its virtual region from which no one can cast it out. The state of crisis, firstly of the global security crisis, then the so called migrant crisis and finally the global pandemics, with all the restrictions they brought about, in many cases revealed that the scapegoat mechanism is working very well in the modern world. In the eyes of many, the other has literally become a demon.

A stranger, alien, carrier of diseases, the one that has come to take what is ours, to destroy our faith and tradition and so on, so on. That is why we are alone in a crowded world; we cannot differentiate between man and demons, around us and within ourselves. We feel the presence of humanity but we cannot see the face of man, we cannot recognize our brother, and that is what haunts us. There is a great story from Christian antiquity which one must recall here. We will finish by quoting with no explanation, since itself is an explanation of what we are and where we are now, as well as what we need.

Abba Macarius said, Walking in the desert one day, I found the skull of a dead man, lying on the ground. As I was moving it with my stick, the skull spoke to me. I said to it, “Who are you?” The skull replied, “I was high priest of the idols and of the pagans who dwelt in this place; but you are Macarius, the Spirit-bearer. Whenever you take pity on those who are in torments, and pray for them, they feel a little respite.” The old man said to him, “What is this alleviation, and what is this torment?” He said to him, “As far as the sky is removed from the earth, so great is the fire beneath us; we are ourselves standing in the midst of the fire, from the feet up to the head. It is not possible to see anyone face to face, but the face of one is fixed to the back of another. Yet when you pray for us, each of us can see the other’s face a little. Such is our respite.” The old man in tears said, “Alas the day when that man was born!” He said to the skull, “Are there any punishments which are more painful than this?” The skull said to him, “There is a more grievous punishment down below us.” The old man said, “Who are the people down there?” The skull said to him: “We have received a little mercy since we did not know God, but those who knew God and denied Him are down below us.” Then, picking up the skull, the old man buried it (The Sayings 1984, 136-137).

Conclusion

Pope Francis’s namesake whose life and words were the source of inspiration in writing Fratteli tutti encyclical, St. Francis of Assisi, in a trully prophethic book thad both announced and denounced many pathological aspects of reality which we are living in, was presented as the role model of a new militant and revolutionary that will bring about change and heal the sickness of the modern world by posing against against the misery of power the joy of being, a joyous life, including all of being and nature, the animals, sister moon, brother sun, the birds of the field, the poor and exploited humans (Hardt & Negri 2000, 413). It brings hope to know that such a militant is sitting on the lofty and sublime throne of the Apostles and that he is calling us to heal and renew ourselves and the world in the divine mystery of fraternal love.

Poštovani, da biste nastavili sa čitanjem naših premium sadržaja, neophodno je da odaberete jedan od planova pretplate.

Već imate nalog? Ulogujte se