This article was translated using a human-assisted ChatGPT process. We’re continuously improving the accuracy and tone of our translations. You can read the original here.

***

Football, bloody hell.

That’s how Alex Ferguson summed up the events of a football match one night in May, 26 years ago. A match many still carry vividly in their memory. In it, Manchester United were trailing Bayern at the 90-minute mark, but scored twice in stoppage time to win the European title.

It was one of those events where years later, people remember exactly where they were when it happened. And those who missed it and heard about it afterward always feel like they lost something. Moments like that go beyond football — beyond sport.

April 17th this year wasn’t a Champions League final. But the plot and twists were even more complex and thrilling, and I’m sure no one who spent Thursday night watching Manchester United and Olympique Lyonnais regrets it — nor will they forget it anytime soon.

For those who somehow missed it, here’s the shortest version:

To reach the quarterfinals, both teams needed a win. United scored early, had a 2:0 lead and full control with 20 minutes to go, and missed several chances to seal it. Then, in their own box, two chaotic moments in five minutes and Lyon leveled. In the 90th minute, Lyon went down to ten men, but in extra time they scored not once but twice — leading 2:4 by the 108th. United cut it to 3:4 from a penalty, but as the 120th minute began, they were still behind.

Then, in the space of 90 seconds, the Red Devils scored two more and won 5:4 — after nearly 140 minutes of football.

Déjà vu?

90 seconds between these two emotions 🤩✨ pic.twitter.com/AaeCkOtG1P

— CBS Sports Golazo ⚽️ (@CBSSportsGolazo) April 17, 2025

Not like we didn’t see it coming

The worst kind of football is when one team is far better than the other — and knows how to punish them.

When two weak teams face off, the only hope is that at least it’ll be comical or chaotic.

With two genuinely strong teams, it all comes down to how they match stylistically — which is why we’ve spent the last few years suffering through Guardiola vs. Arteta duels, while this year’s UCL semifinals offer up such mouth-watering clashes I can’t even decide whether to write one piece or two about them.

But the best matchups often come from teams that have real strengths — and real, obvious flaws. In football circles, the shorthand for that is: Europa League level.

That’s why the UEL — which for most of the season is clearly a step below the Champions League (and the Conference League is just chaos until the very end) — suddenly becomes the best viewing once we get to the last eight.

Whoever’s left is strong — but every one of them has clear weaknesses ripe for punishment.

And when one of those teams is as wildly unbalanced as Manchester United this season? The potential is endless.

When Ruben Amorim’s side plays (and honestly, it was like this under his predecessor too), there’s no lead that feels safe.

Remember — under Erik, they blew a 2:0 lead against a fourth-division side and a 3:0 lead in the 70th minute against a second-division side.

But when they’re focused — and in recent years, that tends to happen in the cups — they can crawl out of the deepest holes.

That crazy ending in Lyon, where Zirkzee scored what should’ve been the winner — only for his team to somehow blow it in the 95th minute — set the perfect stage for a thrilling second leg.

(How does a team made up of adult athletes not know how to waste time with the lead? What are they even training for?)

Lyon had scored and conceded in stoppage time against Hoffenheim (2:2), United went from 2:0 to 2:3 in Porto before Maguire rescued a point in stoppage time, they had turnarounds against Glimt and Plzeň, gave up a win to Rangers in the 88th minute — only for Bruno to take it back in stoppage time, all of that just in the group stage.

Then both teams won convincingly in the Round of 16 — but only after scoring twice in the final five minutes.

United is, on paper, the stronger team — but remarkably good at self-sabotage.

Lyon, meanwhile, has several serious weapons ready to exploit that.

The hosts were all-in on this competition. The visitors had a coach who’s only allowed to work in Europe for the rest of the year. We knew it wouldn’t be boring.

Basketball on the pitch: lob pass or pick’n’roll

Let’s talk tactics for a second — teams in the Europa League are generally below Premier League standard.

I’d even say that West Ham and Wolves aren’t any worse than the average UEL quarterfinalist — and they’re clearly worse than at least 15 other Premier League clubs.

But United’s strong European record this season (7-5-0 overall, 7-2-0 since Ten Hag’s departure) is largely due to one factor: intensity.

On the continent, that level of pressure just doesn’t exist the way it does in England.

Amorim has often spoken about his team’s biggest issue in England: they can’t carry the ball out from the back without stress.

That’s because of the instant pressing that’s standard in the Premier League.

As a result, they usually do better against teams that let them build — while pressing-heavy sides like Bournemouth, Spurs, and Brighton tear them apart.

The root problem is a lack of players who can handle pressure in the defensive half — including Casemiro and Ugarte.

And it’s made worse by the long absences of Martinez and Shaw, the two most natural solutions.

This leads to Bruno dropping very deep in buildup, which makes him basically unusable as a No. 10, and to full-backs playing scared — starting too deep, clogging space, and offering little.

Later on, they’re slow to join the attack, and conservative when they do.

That leaves attackers — especially Højlund, who doesn’t drop back like Zirkzee — and Garnacho cut off for large chunks of the match.

Solve the first phase and you’ve solved over 50% of the problem.

In the Europa League, this problem shows up less — teams rarely have the fitness for sustained high pressing.

Defenders have more time on the ball — and most of them know what to do with it.

Full-backs can push higher and get involved in attack. Bruno doesn’t need to drop back as much. The team holds shape in the final third.

United has other weaknesses too:

None of their central players are good at progressive passing (which is why Bruno drops deeper).

None of the healthy players are one-touch specialists (Zirkzee is injured).

Nobody offers serious pace (Rashford is out, Garnacho is the only threat in the current squad — and even he isn’t elite-speed level).

And Højlund isn’t the type of striker who can hold up play or dominate aerial duels.

Amorim is open about all this in the media, and Thursday’s game made many of these flaws visible — though not as glaringly as they sometimes are.

“I was watching again the ‘99 documentary for inspiration for these moments. It was a great night.”

Ruben Amorim enjoyed that one 😁

🎙 @julesbreach | 📺 @tntsports & @discoveryplusUK pic.twitter.com/7aXrp27ruX

— Football on TNT Sports (@footballontnt) April 17, 2025

From the start, Amorim targeted the space behind United’s full-backs — especially on the right — with passes from Mazraoui and Casemiro to Bruno.

The first goal came from exactly that: Maz waited for Bruno to pull Tagliafico out of position, then burst forward.

The Argentine was so late closing him down that even Bruno’s unusually poor first touch didn’t ruin the move.

The ball was passed on to Garnacho, and Ugarte made the late run from deep.

On the other side, United relied in the first half on a kind of improvised pick’n’roll between Dorgu and Garnacho — which often left the Argentine running at the slower Veretout.

Garnacho kept winning those races. United advanced easily and entered dangerous territory.

It took Lyon a good 20 minutes to mount a real threat, and they did it in a very simple way — linking Cherki with players on the right side, mainly Veretout.

Throughout the game, United’s defense would lose track of Cherki just as the ball went to another Lyon player — and that player would then find the yards of space opening ahead of Rayan with a simple pass.

That pattern worked well in the first half.

And once the ball got into United’s penalty area, they often struggled for minutes just to clear it.

That’s where Lyon’s consistent possession edge came from.

No surprise, then, that the two most exciting moments of the first half came from that dynamic:

Cherki’s solo run through the entire defense in the 30th minute, and Bruno’s volley off the crossbar in the 35th.

Even the second goal followed the same formula — though it started with a rotation (Maguire to Dalot), the sequence was familiar.

Domination… and a storm on the horizon

The first substitution came at halftime — and later we learned it wasn’t planned.

Luke Shaw was expected to play just 30 minutes (Amorim is very precise about managing minutes for players returning from injury), but Mazraoui had to leave suddenly due to a family emergency — same with Lindelöf.

We don’t have confirmation, but there’s strong suspicion it was a burglary — not uncommon in that part of England while players are away for matches.

So Yoro switched to right-back, and Shaw took over as left center-back.

That changed the dynamics immediately — Shaw didn’t surge forward as much as Yoro, the defensive line’s shape improved, and the first phase of possession got more stable.

United were in full control until Lyon’s subs came on.

Even though United had the ball deep in their own third at times, a clean counter could explode at any moment. Like in the 50th minute, when Shaw forced a turnover, Højlund played a perfect ball to Garnacho, who did everything right — the run, the dribble — until the shot.

But he hesitated. And when a striker slows down, the keeper gets a clearer read. Garnacho paused for just a moment, likely surprised at how easily he’d gotten into a clean chance.

Between 2:0 and 2:1, United played with real confidence — Garnacho, Højlund, even Dalot were pulling off things they hadn’t managed in over a year.

Bruno even tried a rabona on the counter.

It was classic transitional football, United’s preferred environment for years — the kind of game their opponents rarely allow.

Fonseca is an experienced coach, and he saw the match slipping away if he didn’t react. So he changed things. First came Lacazette and Tessmann to stabilize both ends of the pitch. Then, midway through the half, he brought on Malick Fofana — who turned out to be the key figure of the game.

He’s my neighbor from Aalst (and if you’re ever there, I’ve got a great pizza place to recommend), signed from Gent for big money, and a huge talent.

In this match, he tore United’s defense apart — and if his teammates had followed his lead, they’d be preparing for Bilbao right now.

Before that, during United’s stretch of dominance, Lyon had already picked up on something:

United’s defense struggled badly in chaos inside their own box — so the visitors made sure to create more of it.

But here’s the thing: in those 20 minutes, United had the match served to them on a platter.

They could’ve easily taken their two early goals and added two or three more.

Backheels, spinning defenders, open looks, missed cutbacks — the hosts had no fewer than six chances to finish off a side whose two key players — Tolisso and Tagliafico — were already on cards and repeatedly exposed.

Slapstick that won’t end

The collapse started with sheer stupidity — as it so often does with Manchester United in recent years. They had possession, recycling the ball, getting back into shape. Then Bruno floated a pass, and the ball grazed off Casemiro’s arm. Most refs would’ve let it go — the ball was headed toward two unmarked United players and barely changed direction. But Schärer wasn’t in a forgiving mood. Almada — who had already caught Onana sleeping from a nothing position in Lyon — swung it into the box. A messy scramble followed. The visitors reacted faster, and just like that — out of nothing — the match was flipped on its head.

Noussair Mazraoui and Victor Lindelof had to leave Old Trafford at half-time to address urgent family issues. #mufc say both matters are entirely independent of each other and the players are both fine.

— Samuel Luckhurst (@samuelluckhurst) April 17, 2025

All that confidence evaporated instantly. Onana started panicking, booting it straight back to Lyon like he so often does in the Premier League. The away end came alive. The mood flipped. Between the two Lyon goals, just four and a half minutes passed — and in that span, they had four good chances, more than in the previous 70 minutes combined.

The second goal was just as absurd. Yoro had taken a hit — blocked a low shot with his head, Vidic-style — and needed treatment. He stepped off the pitch, dazed. The defense collapsed inward. As the young Frenchman returned to his spot, Fofana fired up his dribble engine. His mere presence on the left wing reshaped the geometry of the match. Yoro rejoined mid-attack, but the defense stayed narrow. Maitland-Niles was left wide open on the far side. Fofana found him. He nodded it toward the near post, where Tagliafico nudged it over the line. Onana, flat-footed, was too slow to react. Lacazette slammed in the rebound for good measure — but it was already in. Again: nine United players in the box. All watching.

I’ve described these goals in detail for a reason. This stuff can happen to anyone — but not this often. Manchester United concede goals like this 30–40 times per season — goals where two, three, sometimes five or six players just switch off. And no one else in the league gives up more of them combined. That says a lot. It’s a mentality issue. Fixing that will be Amorim’s biggest job — and I don’t mean in the next few weeks.

Before the 90 minutes ended, two things stood out: Tolisso’s second yellow, which left Lyon a man down for the next 45 minutes. And United’s substitutions. After Shaw, the first major change was Mount and Mainoo coming on for Ugarte and Højlund. At that point, a lot of people thought Amorim had lost the plot.

The first period of extra time felt like pure attrition, Survival of the Fittest — a perfect argument for those who think we should scrap the extra 30 minutes altogether.

Both teams dragged themselves across the pitch, aimless, coughing up possession. Whoever had the legs could gain 40 yards by default. Lyon had a growing problem — Cherki was running on fumes, especially after the Maguire tackle that got the defender booked. (A fair foul — half the team had already dropped out.)

Then in the 100th minute, Amorim made the move: Garnacho off, Eriksen on. Dorgu off, Amass in. That… was the moment. The moment it felt like Bate Borisov vs. Russia again. Bruno and Eriksen as a duo made sense — but who’s playing up top? Casemiro had already logged 110 minutes — and he’d basically just come out of hibernation. We all know Eriksen’s situation. And on the pitch now were three players with limited fitness and one with just a single senior appearance — in the most important 20+ minutes of United’s season.

UNITER WILL NEVER DIED, congrat manu for your’re shit goal , fuck Garna for that miss , you gaves us pain heart 😭😭 pic.twitter.com/zbv1NP82Eo

— Amad (@Amaddiallo_19) April 17, 2025

Who knows how things would’ve played out if disaster hadn’t struck. At that point, the most advanced player was Mainoo, with Bruno and Mount just behind. The third disaster came from a bizarre situation: Dalot burst into the box, slipped as he tried to cross, and knocked the ball out for a goal kick. Lyon’s keeper launched it long, and after a deflection, Maguire tried to play it toward Mount — but the referee got in the way and blocked him off.

Lyon regained possession in what looked like a harmless moment and spent the next 30 seconds recycling the ball across the pitch until Tagliafico slipped a pass that bypassed three United players near midfield. Fofana accelerated, carried the ball into the box, and it rolled to Cherki. He no longer had the legs to run, but he had everything he needed to shoot — 2:3.

And the clean look? Dalot made sure of that too — crashing into Fofana from behind, which sent him flying into Shaw, knocking both down like something out of slapstick (thankfully, no injuries), then kept running and still managed to miss the angle to block the shot. Why Always Us? No, seriously — for a neutral, Man Utd has to be the most entertaining club in football. You don’t get this anywhere else.

Thoughts run like ships

That happened in the 105th minute, and Amorim got his two minutes to lay out the plan: Maguire goes into the opposing box — because he’s the only one who can score with his head (his words); Mainoo plays as a second striker — because he’s not fit enough for long sprints, but excellent in tight spaces; Bruno and Eriksen act as dual playmakers; and the game plan is simple — camp around their goal and lump it in when needed. Crystal clear.

Fonseca had a more original plan — his players would throw themselves to the ground and pretend to be injured. Never seen that before. Cherki went down after 33 seconds, because at that point he genuinely couldn’t move anymore — and God forbid you use your sub during the break. Once play resumed, Maitland-Niles went down after 31 seconds. I won’t go on, but actually I will. The show continued with a long ball turned into Fofana collapsing in the box between Shaw and Yoro. The ref booked Fofana for simulation, though Shaw had clipped him.

Lacazette stepped up and finished with ease — waited for Onana to move and sent it the other way. 2:4 in the 109th. Rock bottom. No hope left. Messages started coming in, but the phone was still on the charger. Turns out, the match was only just getting started. First rule of sports — don’t jump to conclusions until it’s actually over.

It was the beginning of heroic monumentalism, the moment when those with real mental steel take charge. And there are few players in the world with more of it than Casemiro. Just before that penalty, the ball that triggered it had come from him. But he’s not here to dwell — he’s here to win. He won the aerial duel, Maguire flicked it on, and Case was the first to reach it again — only to get hacked in the leg. VAR, for once, told the Swiss referee to open his eyes. The check, Bruno’s inevitable execution (the keeper really gave it everything), and the restart took 49 seconds. When the ball was back in play, it was 114:25, with only 2 minutes and 2 seconds officially left in the second half of extra time. Surely the ref would make up for it.

By now it looked more like a playground shootout than a proper game. You remember that — ten vs. one, one goalie, everyone else volleying, switching keepers when it goes out, and you’re out if you concede ten. Everything was in the air. Harry was a force. There was a solid penalty call for a foul on him just a minute after the restart. Every ball was his. The game had boiled down to this: they want to boot it, we want to aim it right and launch.

And yeah — Duje Ćaleta-Car had come on.

At 117:53, after Bruno missed one, the camera found a kid crying. No time left for anything. He looked maybe nine, around my own kid’s age, who was off on a holiday scout trip. Thank God my wife didn’t see the crying kid — she wouldn’t recover until Easter, when ours comes back. Back in the fall, I bought him a jersey. No. 47. Kobbie Mainoo. One of his coaches is a United fan. Good kid.

At 118:55, Onana — for the first time in two years — finally did what he was brought in to do: took the ball near midfield and made a clean pass. To Bruno, to Case, to Mainoo. A hop, a cut to the right, placed into the side netting — almost a carbon copy of the Liverpool goal last year. 4:4 at 119:09.

Penalties, then? Not ideal. The Brazilian is tall and reads well, but Onana tends to dive too early. Still, at least Ruben was smiling. He’s not a grouch — but chances to smile have been rare since he arrived. No. 47, Kobbie Mainoo. He’s been playing like himself again since cutting his hair. Celebrated just like Zirkzee — a nice nod to his injured teammate. Looks like the dressing room isn’t as fractured as some think. Five minutes of added time. Time to dig in, like ‘99. Onana plays it to Shaw, to Amass, to Casemiro. Case goes long — Niakhate, solid until then, completely misjudges it. Harryyyyy… OMG OMG OMG. 5:4 at 120:35. No way. Did that really just happen?

At 121:18 they show the same kid again. Still crying — but now it’s something else entirely. Just a game? Sure it is. Wait, hold on — there are still four minutes to play. Probably even more. Focus. Stay sharp. Now Onana’s cramping up. Fair — he did complete those two passes. FINAL WHISTLE. It’s actually over. Bilbao, get ready.

Look at this joy. Shaw and Harry, Gareth’s boys. Kobbie and Garna. Don’t sell your own kids. Period. No. 47, Kobbie Mainoo. Message from Marko. Ten minutes to pull myself together — then off to work.

We’ll never die

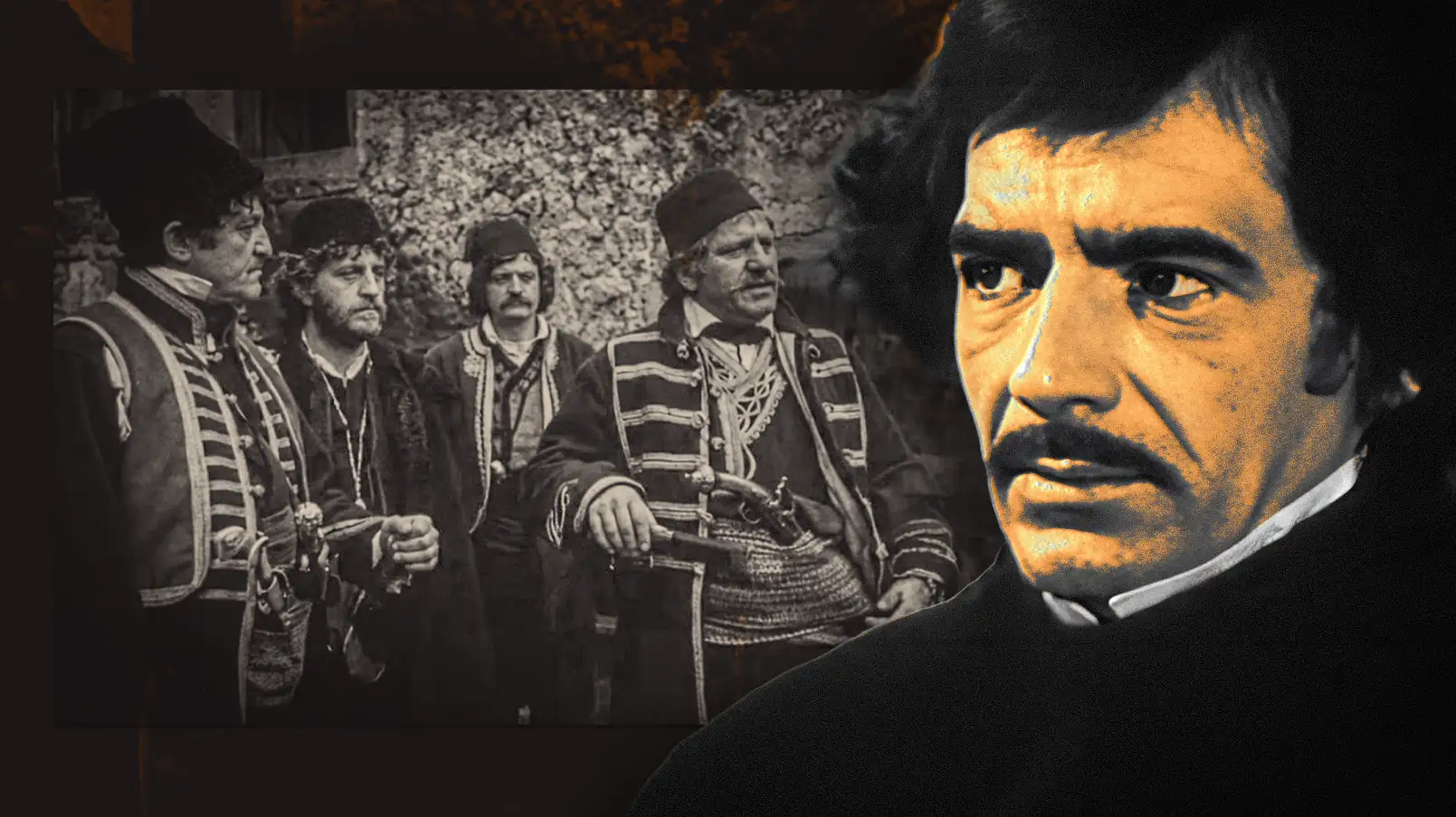

History tells us that in Manchester United’s 147-year existence, there’s only been one other game they won 5:4. It was at Highbury, where the reigning champions beat Arsenal on a cold, foggy February 1st, 1958.

It was the last match the Busby Babes played on English soil — the most legendary generation in British football. They’d won five consecutive youth FA Cups, then back-to-back First Division titles, all while averaging just 21 or 22 years of age. They were seen as the successors to Real Madrid as Europe’s next great dynasty.

That match against Arsenal is still remembered by many as the best they ever saw. The Times’ Geoffrey Green reported it with the words: “Both the crowd and the players were breathless as the teams walked off, hand in hand. It was clear they’d created something to be proud of — something to remember for a long time.”

Four days later, they played Red Star in Belgrade in the second leg of the European Cup quarterfinal. At Old Trafford, they’d come from 0:1 at half-time to win 2:1. In Belgrade, they went up 3:0 by halftime. Zvezda clawed it back to 3:3, but the score held. United advanced. That night, players from both clubs spent hours together in Hotel Mažestik.

The next day, tragedy struck. On the return trip, their plane crashed on the runway in Munich. Among the 23 victims were eight players, two coaches, and the club secretary. Among them: Tommy Taylor and Duncan Edwards, England internationals who had scored three of the five goals against Arsenal.

February 6th, 3:04 PM — when the plane hit a building at the end of the runway — remains the most defining moment in the club’s history. From that day on, United’s red shirts and white shorts were paired with black socks.

Despite a decimated squad and Matt Busby being hospitalized for months, the team — led by academy chief Jimmy Murphy, who’d missed the crash because he was coaching Wales that day — made it all the way to the FA Cup final. With a new generation, including survivors Bill Foulkes and Bobby Charlton, Busby won the FA Cup in 1963, followed by two league titles and the 1968 European Cup. Out of that tragedy and rebirth came the fan anthem “We’ll never die,” adapted from the 19th-century workers’ song “The Red Flag” — later recorded by Billy Bragg in 1990.

United flag is deepest red.

It shrouded all our Munich dead.

Before their limbs grew stiff and cold,

Their heart blood dyed its every fold.

Then raise United’s banner high,

Beneath its shade we’ll live and die.

So keep the faith and never fear,

We’ll keep the red flag flying here.

We’ll never die, we’ll never die,

We’ll never die, we’ll never die,

We’ll keep the red flag flying high,

’Cause Man United will never die.

The song only grew in popularity over time — with every game that felt like coming back from the dead. The ‘99 Champions League final was just the most famous example. Few clubs in world football have as many.

Think of the derby in December when City led in the 89th minute and still lost 2:1. Or Macheda’s goal vs. Villa in stoppage time — my brother still has nightmares about that one. Or Ruud’s comeback in the FA Cup: from 0:2 to 3:2 in ten minutes. Or Garnacho–Højlund flipping Villa again after being two goals down, with ten minutes to spare.

Or Ole’s first dagger in the 98/99 treble run — Liverpool led for 86 minutes, still lost in injury time. Or last year’s FA Cup quarterfinal: United forced extra time vs. Liverpool, then turned 2:3 into 4:3, with Amad scoring in the 121st. Or Van Persie at Southampton, goals in the 87th and 92nd. Or the Spurs chaos of the early 2000s: 0:2 to 3:2, or 0:3 to 5:3.

Or Sheffield Wednesday in 1993, when Ferguson’s first title run was hanging by a thread. They trailed 0:1 until the 86th. Steve Bruce scored twice — the second in the 96th. Fergie and Brian Kidd celebrated on the pitch. Or the Juventus semi in ’99 — from 0:1 in Manchester, to 0:2 in Turin after ten minutes. Yorke and Cole flipped it to 3:2 in the 88th and booked a place in Barcelona.

Honestly, I could go on for five more pages off the top of my head and tell you where I was for each one. Sneak preview: I followed the first Juve semi on Teletext — April ’99, no TV broadcast — staring at a single line: “Man Utd 0-1 Juventus.” Next line: “Del Piero 1.” The second leg was a different story, but that’s for another time. Maybe when I write about watching football during the ’99 bombings.

But let’s get back to the boys in red, white, and black — and their guests from Lyon.

Olympique Lyonnais for beginners

Seven-time consecutive French champions from the early 2000s, Lyon haven’t been near that level in recent seasons. They entered this one with big ambitions. Owner John Textor was determined to bring them back to the Champions League after last year’s sixth-place finish. Over €150 million was spent on new players in the summer — compared to €40 million brought in — with 15 arrivals, including five from the Premier League.

The season started badly — three losses in their first five, including a stinging one to Marseille, where they lost to a team with fewer players after throwing away a lead in the 95th minute. At that point, they were flirting with the relegation zone. But a three-month unbeaten run lifted them to fifth place before the trip to Paris — and fourth in their UEL group.

Winter brought a slump. They lost twice to PSG and managed just three wins from nine games — two of those against dead-last Montpellier. They drew their final two group matches in the Europa League. Major changes followed: seven players left in January, including big names like Zaha, Benrahma, Caqueret, and Gift Orban. Then coach Pierre Sage was sacked.

couldn’t have asked for a better IP plan for Manchester United tonight.

Manipulate Lyon’s midfielders to create and attack space. Namely Bruno—his off-ball movement and intensity were unreal.

Dragged his marker all over the place. pic.twitter.com/894AECbuPE https://t.co/3uAuKKvq5T

— Fathalli (@FathalliMo) April 17, 2025

In came Paulo Fonseca, the Portuguese manager who’d been at Milan before the break. He won three of his first five games. In the fifth, against Brest, he shoved the referee — and was handed a nine-month ban from Ligue 1, which meant his assistant Jorge Maciel, who worked with him at Lille, took over domestically.

Since then, Lyon won four of five and climbed to fourth — within reach of the Champions League. The Ligue 1 table is tight: second-place Monaco and seventh-place Nice are only five points apart. In Europe, they beat FCSB twice to set up the tie with United — hoping to upset the more expensive side.

Fonseca’s squad is a mix of veterans — Tolisso, Matić, Lacazette, Mata, Tagliafico, Niakhate, Veretout — and young blood like Nuamah, Fofana, and especially Rayan Cherki, the enfant terrible of French football. His talent has been well-known since his youth days, but his habits on and off the pitch have kept him from moving on. Of Algerian descent, he’s matured this year — averaging a goal contribution every 90 minutes (12 goals, 18 assists).

Alongside him: experienced Lacazette, ex-Ajax forward Mikautadze, young Argentine Almada, and Belgian winger Fofana. All should command strong transfer fees — except maybe the Arsenal returnee. In the first leg, which Fofana missed through injury, Almada scored the opener, Cherki the second, and Mikautadze gave United plenty of problems as the focal point.

A stoppage-time goal and United’s messy form gave Lyon real hope of going through — and reaching the Champions League either way. Ligue 1 is volatile enough that three solid seasons could stabilize the club financially with regular UEFA money.

A record-breaking season

Since we last checked in on them, back in late February, United have gone through yet another round of turbulence and — somehow — stayed exactly where they were. They were knocked out of the FA Cup by Fulham on penalties, thrashed Real Sociedad at home, and went four league games unbeaten: two wins against bottom feeders, a comeback draw vs. Everton, and a stalemate with Arsenal. Then came losses to Forest and Newcastle, plus a toothless draw with City — a stretch that laid bare the team’s state: defensively improved enough to nullify good opponents, but offensively hopeless, worsened by Zirkzee’s injury.

Amorim’s league record — six wins, ten losses — has brought a media pile-on, even though his cup record stands at 7-4-1. It’s easy to see what’s improving — and what’s limited. And with several key players injured, those limits aren’t going away.

Still, two good things have changed. First, players with major roles who had been out are starting to show up again: Mount, Mainoo, finally Shaw. Amorim is easing them in carefully, prioritizing long-term value over short-term wins. Second, more academy use. After Collyer, minutes went to Heaven and Amass, and Amorim has openly committed to playing more youth in the league. Too bad Chido Obi-Martin got hurt — Zirkzee’s absence could’ve opened the door wide. The U18 stars Musa and Biancheri may now get a shot.

Amorim still sounds great in every press appearance — direct, self-aware, never evasive. He knows exactly what he wants, and just as importantly, what’s holding him back. His post-match interview with Rio and Scholes after the Lyon second leg was a masterclass.

With six league games left, United are 14th with just 38 points and a –7 goal difference — better than only five teams in the league. The loss to Newcastle confirmed what we already suspected: even matching their worst-ever Premier League season (58 points in 2021/22) is no longer possible. Even in a miracle finish, 11th is the highest they can reach. The trio in 8th–10th is ten points ahead. The next-worst seasons to chase: 13th place and 48 points in 1989/90 — a year when the FA Cup saved Ferguson’s job and started the avalanche.

Fortitude before tactics and technique

In times like this, what saves a manager is the character of his team. You’ve probably heard that it was Mark Robins’ goal in January 1990 that saved Fergie’s job — that season, they had three more 1:0 wins, a wild 3:2 vs. Newcastle where they had to lead three times, a replayed 2:1 win over Oldham after a 3:3 in the first, and a cup final with Crystal Palace that ended 3:3 after extra time. The replay was decided by left-back Lee Martin — one of just three career goals — and it was enough to get Ferguson his first trophy in England. In the 23 seasons that followed, he only finished trophyless twice.

Games that launch legacies aren’t just a United thing. Think about Klopp in 2016 — his Dortmund led 3:1 at Anfield with 25 minutes left. Liverpool scored twice and needed one more or they’d be out. The winning goal came in stoppage time. That was nine years ago and three days. Quarterfinals of the Europa League. Scorer? Dejan Lovren — the often-mocked center-back.

Or Real’s comeback against Wolfsburg in the UCL 2016 quarterfinal. Zidane had taken charge of Madrid only three months earlier. They were down 0:2 from the first leg. Cristiano Ronaldo hit a hat-trick. That match opened the door to La Decima — and Zizou’s era of legend.

🙌 Not only did @B_Fernandes8 inspire our extra-time comeback, but he fired United to a historic landmark of Old Trafford goals ⚽#MUFC || @DooFinancial pic.twitter.com/uVwUALB6XM

— Manchester United (@ManUtd) April 17, 2025

Even Mourinho’s rise was tied to a game like that. Porto had already won the UEFA Cup and had a first-leg lead against United in 2004, but it was Costinha’s 89th-minute goal that launched José into the stratosphere. Just three and a half years after his debut.

It’s entirely possible Amorim finishes this season without a trophy — which would mean no Europe next year and a tighter budget (but more time to build, as many will note). Klopp didn’t win the Europa League in 2016 either — he was leading at halftime of the final. But the pieces came together after that — not just with smart sales (Coutinho) and signings (where to even start), but because next time, there was another Lovren. Or an Origi. Someone who stepped up just as time was running out.

Next up is Athletic Bilbao — flying through La Liga, full of in-demand talent, and hosting the final. And when you host the final, you get a little extra love — just ask Dessers, who tore his shirt in rage. Even without that, many still remember what Bielsa’s Athletic did to Fergie’s United. No one ever outplayed them quite like that — not even in a 0:5 aggregate loss.

And if they make it through? The likely final opponent: another Premier League basket case — Tottenham. Spurs are the only team to beat United three times this season. Pep, by comparison, has one point in their last three derbies and no wins in six. But hey — it’s Spurs. And the final is played that day.

Or maybe it’ll be Bodø/Glimt. Norway’s first-ever semifinalist in European competition. Four titles in five years. Revenues almost nine times higher now than in 2019 — steeper growth than the club that knocked them out of the UCL playoff. If you remember, that was Amorim’s Sporting. They already played one wild match — 3:2 last November. If Glimt make the final, it’s guaranteed fun.

Then again, how could it be anything else with Ruben’s Great Entertainers…

Poštovani, da biste nastavili sa čitanjem naših premium sadržaja, neophodno je da odaberete jedan od planova pretplate.

Već imate nalog? Ulogujte se