This article was translated using a human-assisted ChatGPT process. We’re continuously improving the accuracy and tone of our translations. You can read the original here.

That scene alone shows how important—basketball‑important—Radoslav Nesterović was.

As is often the case here, a top athlete’s career—especially for those who came of age in the 1990s—tells a story far beyond sports. His basketball biography reflects everything coursing through the remnants of Yugoslav hoops and stands as a record of an entire generation’s life.

A Slovenian national team player of Serbian origin, he moved to Belgrade in 1992, just as many were leaving. From there he became a EuroLeague champion, an NBA champion, and played for some of the best coaches in Europe and the world (Ivković, Messina, Popovich…). The only one he never worked with was Željko Obradović, though records show he was technically a Partizan junior the season Obradović coached the senior team.

During a rich NBA stretch he suited up for Minnesota, San Antonio, Indiana, and Toronto. The Slovenian national team podium eluded him only as a player, but he later achieved it while leading the Slovenian federation. In American terms, he “checked every box.”

He grew up in the Ljubljana neighborhood of Fužine—once labeled “notorious,” a kind of local “ghetto.” Anyone who has read Goran Vojnović understands why Fužine matters: it helps explain both the many Ljubljančani whose surnames end in “‑ić” and the small‑scale Yugoslav melting pot that produced top‑level sports results.

Fužine, a Living Myth

“There was all sorts of stuff in Fužine. Even Rade Šerbedžija wrote about living here during the war years and how our people lived. But for us kids, sport was everything. Many footballers and basketball players grew up there—Handanović, Ljubijankić, future Slovenia internationals.

There’s no secret: it was a new housing project that started in the 1980s, packed with young families, many from other republics—as was normal in the old Yugoslavia.

It’s like New Belgrade, just smaller, and full of kids. You’d come home from school, do your homework, then head straight down to the court—there were courts everywhere. In that sense Fužine was perfect, and that’s where you became an athlete. Whether you were a hooper or a footballer, the scene was the same: you’d arrive and some thirty‑year‑old just off work would be waiting to rough someone up. That’s where you proved yourself, you toughened up.

It definitely wasn’t what people later claimed. Sure, kids do crazy things, but it was harmless—far from any real crime or “ghetto.” Sometimes groups from Fužine went out together and if they caused trouble maybe the police would say, ‘Look at those Fužine guys moving like a gang.’ I think that’s how the image got exaggerated. I never felt unsafe there.”

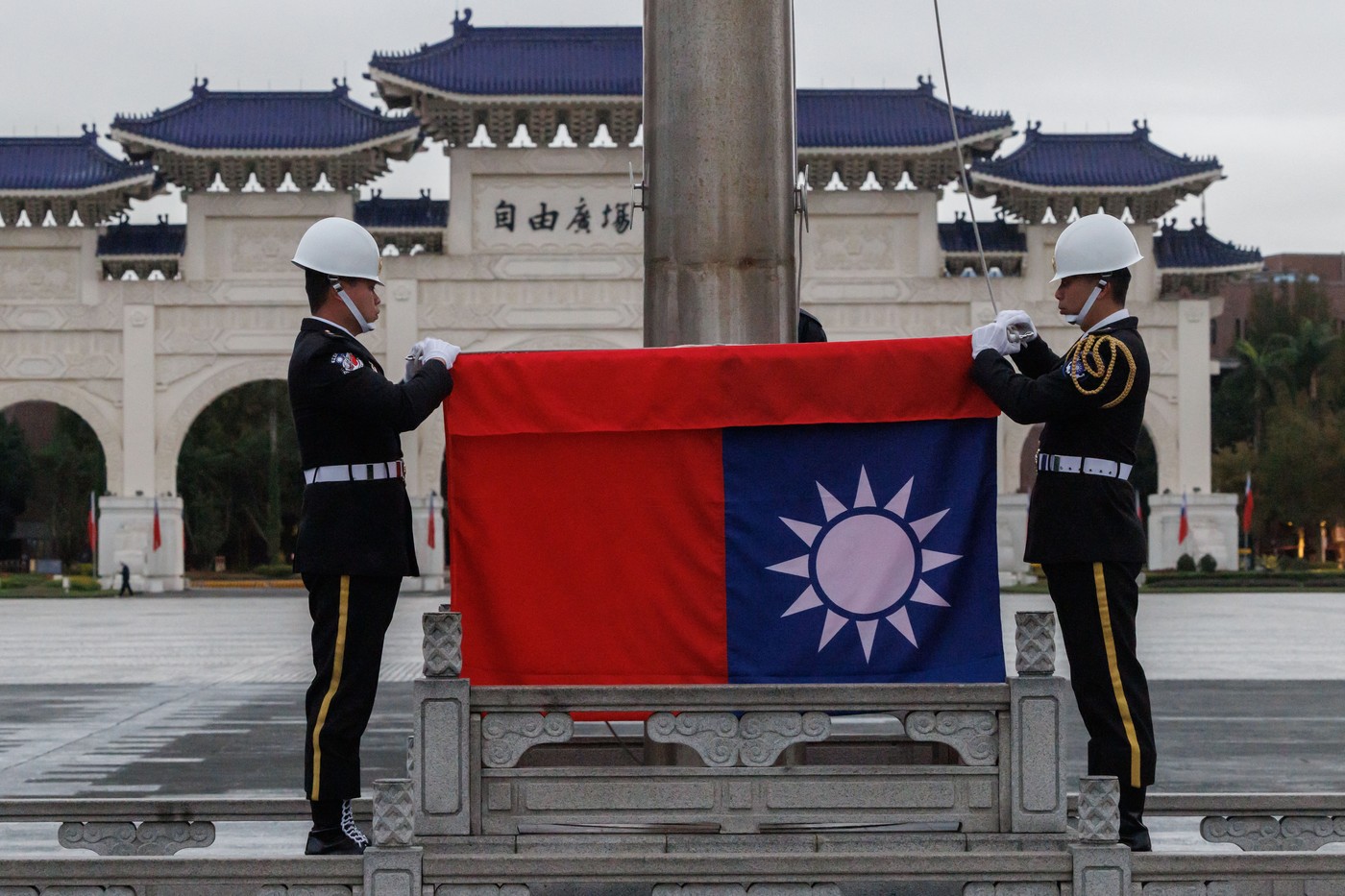

It Was All Yugoslavia

“As a kid did I feel like I lived in someone else’s environment? For us it was all Yugoslavia. Every school break I spent in Novi Sad with my mom’s family or in Bosnia with my dad’s. Summers meant a trip to the coast. It was one country. We played with everyone. We didn’t notice the things that were politicized later in the ’90s when ‘who’s who’ suddenly mattered. Looking back, I’d say Slovenia got over that pretty fast. I never felt pressure because of my background.”

Coming to Belgrade (While Others Were Leaving)

“I was already playing basketball and we went to a tournament—May 1992 in Malmö—where Partizan and Tašmajdan were also present. Novica Ćićić, then Partizan’s coach, and Miša Lakić from Tašmajdan approached me. That’s when I first met guys who are still friends: Kiza Ilić, Ratko Varda, the late Deki Milojević…

We kept in touch over the summer. I came down, did two or three practices, and life just lined up. I didn’t care that the situation was bad.

My logic was simple: Partizan had just won the EuroLeague. If I’m serious about hoops, let me see whether I can hang. You never know until you test yourself against the best. I’ve never regretted it—that move was the best decision of my career.”

“My first coaches were Naser, Nenad Trajković, and Pera Rodić. And I met people who are still my kumovi (godfathers) and friends. I mentioned Ratko Varda, Kiza Ilić—there’s Stragi, Mića Berić, many others…

Those relationships are what remain. The NBA and the trophies are great, but the biggest success is that I stayed on good terms with most teammates. Because of that, joining Partizan was a turning point both professionally and personally.

It couldn’t have been easy for my parents, but we didn’t see Belgrade as a foreign place. My late grandmother lived in Novi Sad, most of my relatives were there, and I was thinking only about basketball.”

“But problems hit quickly. I left, and at one point phone lines to Slovenia were cut. Three months passed without talking to my parents.

I was living behind the Putnik Hotel on Gramšijeva Street. One day after school I saw a familiar figure across the road—my dad had shown up. He hadn’t told me because he couldn’t; he only roughly knew where I lived and when classes ended, so he waited. When I tell my kids that today they think it was dinosaur times—‘Why didn’t grandpa just text you?’

Back then everyone knew Partizan was Europe’s best. Crvena zvezda too, of course. Coaches like Naser and Pera were here; Fikus Badnjarević was over there, coaching Peđa Stojaković… In the end that’s where I learned the most and made the biggest jump.”

Partizan and First Dreams

“At Partizan I realized I could maybe make a living from this sport. Expectations were different—we didn’t think about the NBA. Divac and Dražen were there, Paspalj had come back, and that was it.

Today everyone dreams NBA. My dream was simply to play for the Yugoslav national team. I remember during one set of qualifiers, while Serbia was under sanctions, Saša Danilović came to train with us juniors in Pionir. To me, seeing him was a bigger thrill than if Michael Jordan had been on the other side. Danilović showed up—are you kidding me? Later we played together at Kinder, unbelievable…

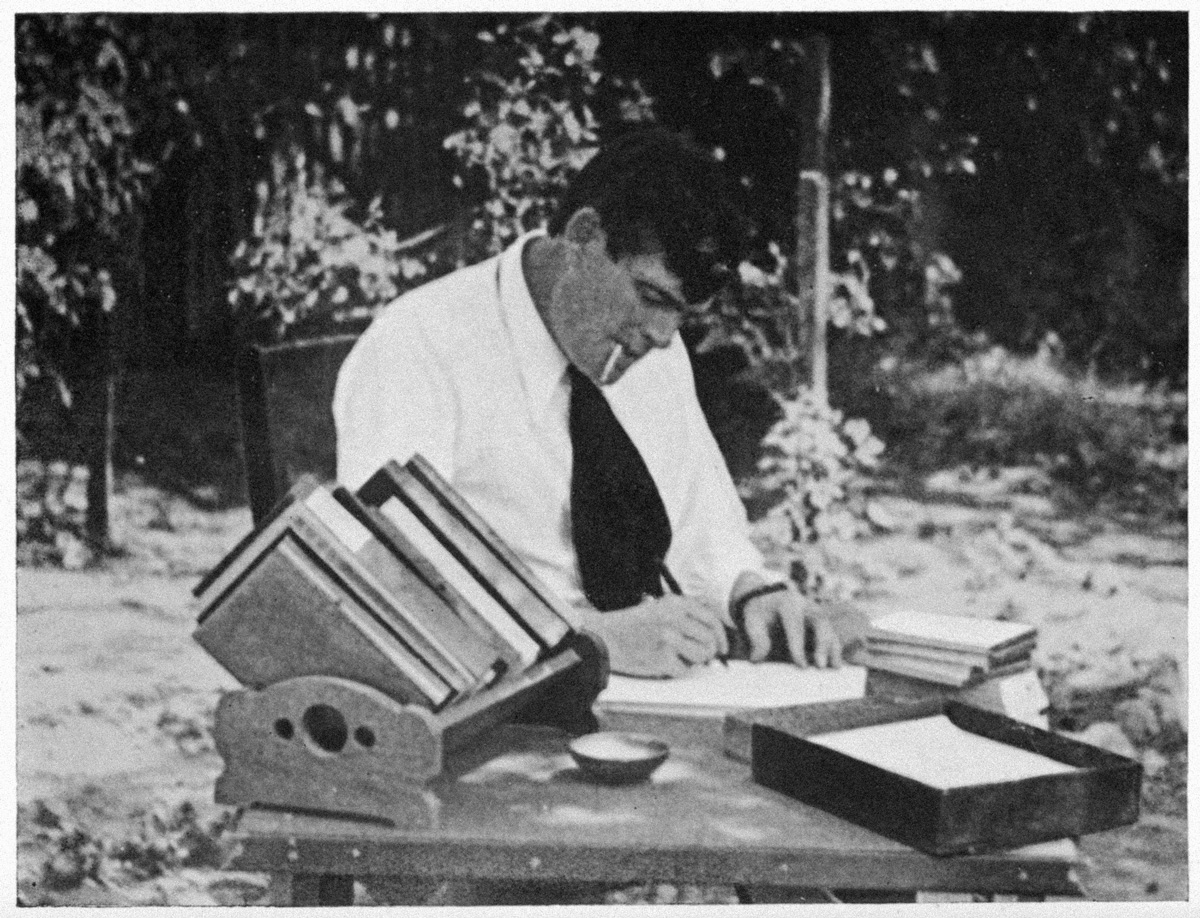

/Foto Nebojša Babić

The country was closed, and we played only among ourselves. That junior league had several future NBA players: Peđa Stojaković, Predrag Drobnjak, and me. EuroLeague‑level guys were everywhere. I’m not sure any European league today can say that eight junior teams produced so many NBA or EuroLeague players.

Rade Šerbedžija wrote about living here during the war years and how our people lived. But for us kids, sport was everything. Many footballers and basketball players grew up there—Handanović, Ljubijankić, future Slovenia internationals.

There’s no secret: it was a new housing project that started in the 1980s, packed with young families, many from other republics—as was normal in the old Yugoslavia.

We played because we loved it. After games we’d hang out—team rivalries were not a topic. Nobody talked NBA vs EuroLeague; the only question was how to scrape together a summer trip to Montenegro for a week…”

After that season Peđa went to PAOK under Duda Ivković, and they later invited me too. Maybe I wouldn’t have left, but Partizan’s preseason came with a new coach, Željko Lukajić. He was great with me, but some other staff favored veteran signings over us kids. I always listened to my gut: it didn’t feel like the right path—and it didn’t seem fair.

We weren’t playing in Europe at all. If youngsters don’t get minutes then, they never will. Otherwise I’d probably never have left Partizan—it was great there.”

Duda, Željko, Danilović, Savić…

“I was in Partizan’s youth system. Željko Obradović would come watch games. I never worked with him directly, but having him in the stands was a big deal. I’m not sure kids today grasp that level of respect.

Then I moved to PAOK—and there was Duda. Everyone both feared and revered him. He blazed a trail for Serbian basketball.

Zoran Savić was there, too; later we were teammates at Kinder. Imagine telling Savić, ‘I’m not doing that.’ If he said, ‘Bring me water,’ I’d sprint, honored that he asked me.

Times are different now, but I feel the respect for elders and pioneers was greater back then.”

Return to Slovenia

“I got Greek citizenship but there were more bureaucratic hiccups, so I went back to Slovan for a year and a half, then moved to Olimpija for two seasons.

The 1997 EuroLeague Final Four was strange: I played one game, sat the next. Three coaches changed that first season—confusing for a young player.

The next year Zmago Sagadin arrived and contract talks came up; offers went around, and I ended up the only one who didn’t sign.

I’ve always aimed higher, so I decided to leave—not because it was bad; it wasn’t—but that’s how things evolved. I barely played: two or three games and a national‑team match versus Italy. I recall one EuroLeague game when everyone was sick and I scored about 20.

That season left me shaken and low on confidence. Then legendary Kinder showed up with an offer. Everyone said it was a mistake except young agent Rade Filipović: ‘Forget them. Messina is top‑class, and more important, you’ll have Zoki and Sale Danilović to guide you…’ And that’s exactly how it went.”

Traning the Next Day

“I remember: Monday was our day off, and Zoki said, ‘Training at ten tomorrow.’ I show up at ten, and it’s not a three‑hour grind—just one hour, but in that hour you learn more from Zoki than from a hundred coaches in a hundred years. That’s when I understood professionalism.

Seeing those two, plus Rigaudeau on the roster, I knew I had to push myself harder than ever.

We played great that season. Early hiccups, then it clicked. Before the Final Four we had the infamous brawl series with TeamSystem—Europe’s two strongest teams—so reaching the Final Four was already huge. Once there, veterans like Sale, Rigaudeau, Savić tipped the balance.

We beat Partizan easily in the semis, battled AEK in the final, and won. One of the best things in my life—Barcelona, half of Bologna moved there to cheer, plus Partizan fans, and my first taste of something that big. I was still a kid and didn’t grasp how rare titles are—until we lost the next year’s final to Žalgiris.”

And Then the NBA Arrives…

“The Italian season ended; we fell to Varese in the semis—Sale was hurt, others too. The next day I was on a plane to Minnesota. After landing they sent me to Houston, and 48 hours after dinner in Bologna I was on the floor in Houston.

Coach told me to enter in the second quarter—against Barkley and Pippen. It was that weird lockout season, everything moved so fast I couldn’t process it.

The NBA then wanted physically strong centers to battle Shaq: Yao Ming, Alonzo Mourning—everyone was big. It was a physical league.

I recall my first season in San Antonio: we played the Lakers in the playoffs, Game 5 at home. Tim Duncan scores, 0.4 seconds left, then Derek Fisher hits the dagger. We lose Game 6 in LA. Final score was 74‑73… Today teams post that by halftime.

Every basket was a fight. When Jordan dropped 63 on Boston people talked about it for months. Now fifty points is hardly news.

I played that way because the era demanded it. If I played today, I’d adapt. Same with the GOAT debate: each era has its heroes. For me Jordan is the best, but I love watching Larry Bird on old tapes: couldn’t jump, looked slow, but could do everything—times ten. He’s Jokić before Jokić, or Jokić is a new Bird.

Later in Indiana, Bird was team president. First time I saw him, I thought how huge he is—bigger than on film. Then you wonder how big the guys who fought him were: the Bad Boys, Rick Mahorn, Bill Laimbeer.

In Minnesota I played with Garnett—if he conceded a basket he’d explode. He wanted to win so badly he sometimes went overboard. His attitude was, ‘Maybe you’ll score, but you’ll pay for it.’ He gave everything, and as team leader he wouldn’t let you give less.”

When I Took Gregg for Ćevapi

“Popovich waited for July 1—league rules forbid contacting players on other teams before that. I was in Ljubljana when Paspalj called: Gregg wanted to talk. I took him for ćevapi.

What did we discuss? Ćevapi and basketball (laughs). He asked if I’d join San Antonio. He’d spoken to Duncan, all was fine there. He told me how he saw the team and asked if I accepted. What could I say to Gregg—‘No’? (laughs)”

The Pop Factor

“Even then some US coaches ‘feared’ star players, letting them call the shots. With Pop it was always his show. I started some games, came off the bench in others; sometimes I played, sometimes not. Whatever happened, he’d come over, explain the decision, the goal, and what he expected.

He talked to you like a person, and that matters. Elsewhere you might just find yourself benched and wonder why. With Pop everything was clear.

The Spurs were a champion‑level international squad. It wasn’t easy: different system, Duncan unlike Garnett. Statistically I’d probably have done more by staying in Minnesota, but I don’t regret it.

Most important, I made friends I’m still in touch with. We recently gathered in Paris—Žare Paspalj came, old Spurs and Pacers guys, plus Manu Ginóbili, Sean Elliott, David Robinson…

It’s nice they haven’t forgotten me. San Antonio was formative on and off the court, just like Partizan.

Pop has that European touch. It wasn’t always gentle—he’d blow up at times—but more often there was laughter. On road trips he’d book a restaurant between games and tell players: ‘Whoever wants to come, come.’ Twelve‑plus guys won’t show, but six or seven will. While I was there I thought that was normal; after switching teams I realized it wasn’t.

That bonding helped, especially after losses. Five of us together handle it better than each guy stewing alone. Duncan seldom came—wherever he went fans mobbed him, so he preferred quiet before games.”

Tim Duncan, the Phenomenon

“He’s a great guy. Not weird at all—just quiet and reserved, always ready to help. Relaxed, willing to joke at his own expense.

People forget that squad also had a player with more rings than Michael Jordan: Robert Horry. He hit the three when we went up 3‑2 in the Finals against Detroit and pulled out that series.”

Maybe Toronto Was Even the Best…

“Toronto’s a fantastic city with lots of our people. I could have stayed without missing home. Life was good—my first child was born there.

They love hoops—arena always sold out. Chris Bosh was there, Anthony Parker from Maccabi, Garbajosa, Calderón, Carlos Delfino, then Hedo Türkoğlu one year… Results varied, but overall it was good.”

And Finally Back to Duda—The Last Stop

“By then I was a veteran, two kids, third born in Greece. Practices were hard, though Duda spared the older guys. I was 34‑35, playing with Teodosić, Kešelj, Spanoulis…

I was lucky: shared courts with Savić, Danilović, Garnett, Duncan, Chris Bosh, Spanoulis. Money can’t buy that—either it happens or it doesn’t.

Then I injured my shoulder before the playoffs—season over. I decided: I’m driving the kids to school. They’ll never be four or five again, and playing another year or two wouldn’t change much—might even bring a worse injury.

I love basketball, but when younger, better guys arrive—why stay? You need to step aside at the right time. We didn’t get that in our day, especially in Slovenia.”

Slovenian National Team

“Maybe funds should have been set aside for a top‑level coach. There’s regret we didn’t achieve more, but that’s how it goes.”

How Igor Kokoškov Arrived

“The idea was to bring a coach who could better integrate Goran—our only NBA player then—and who understood our mentality. Many here were skeptical.

I’ve known Igor since my Minnesota days. You’re new in the NBA, wandering through cities, know no one, then we play the Clippers and someone in a Clippers shirt walks up: ‘Hi, I’m Igor.’ I thought, ‘What’s Igor doing here?’ (laughs) That’s how our friendship started.

In the national team, conditioning coach Šile—Miljan Grbović—was crucial. From the shadows he lifted everything: loosening, tightening, picking you up when you’re down, grounding you when you’re flying. That’s our mentality…”

The Adriatic League

“There’s a big economic side. The countries split into markets of two‑to‑five million people. Olimpija in Slovenia or Cibona in Croatia can’t generate the money or marketing space the whole former Yugoslavia can. The league’s purpose was developing young players. The idea is brilliant—just needs different management.”

The NBA Coming to Europe

“I can’t say much—NDAs bind me. That leak wasn’t accidental. Knowing the NBA, they’ve researched thoroughly. More questions than answers remain.

Basketball circles are excited yet confused—even scared—except maybe clubs like Real Madrid that know more. Business, on the other hand, is thrilled and racing ahead. While some ask, ‘Who’d pay 500 million for a franchise in a league that doesn’t exist,’ in a city like Amsterdam with no basketball culture, others scramble not to miss out. You wouldn’t believe the interest from big global players—financial institutions, funds, agencies.

Who are you obliged to, what can you reveal?

Honestly, not much (laughs). I’m part of a group exploring possibilities. I can say there aren’t many public names involved. From our region it’s only me and Mr Vuk Mitrović—though he hasn’t lived here for almost 30 years.

Our ‘working group,’ let’s call it, includes many top executives—or former ones—from finance, investment funds, banks, major football clubs, global corporations, sports agencies, plus a few ex‑players and coaches. A very interesting crew; I’m happy to work on the project.

What kind of project, what’s the goal?

Again, can’t go into detail (laughs)… Let’s say anything from creating a ‘European NBA’ franchise in an unexpected location to running one where everyone expects it—and everything in between. Not sure I haven’t already said too much for my contract.

My personal hope is that it finally brings order to European basketball and gives future generations a clearer development path.

Poštovani, da biste nastavili sa čitanjem naših premium sadržaja, neophodno je da odaberete jedan od planova pretplate.

Već imate nalog? Ulogujte se